Supporting Japanese art of past and present -- Professor Yuji Yamashita talks about contemporary bijin-ga and “New-shin-hanga”

Yu Miyazaki, a Japanese-style painter who is currently much attracting attention, is now producing a new bijin-ga (portraits of beautiful women) with artisans who have inherited traditional woodcut printing techniques. (Click here for the interview article with Yu Miyazaki.) Yuji Yamashita, professor at Meiji Gakuin University known as “the Chief of the Japanese Art Support Team,” has been watching over Miyazaki's career since the beginning. We asked Professor Yamashita about the meaning of producing bijin-ga in modern times, in light of the history of ukiyo-e and shin-hanga (new woodcut prints).

Recent trends of “bijin-ga” in Japan

――First, I would like to ask you about the recent trends in “bijin-ga” in Japan. I have the impression that the term “bijin-ga” has become more common in exhibitions and publications, especially in the last few years. I feel that there are more young artists who paint bijin-ga than landscapes or still lifes.

The history of the term “bijin-ga” is actually surprisingly short, although the word “bijin” ("beauty") has been used for a long time and many “beauties” are depicted in ukiyo-e. Moreover, there is no word equivalent to “bijin-ga” in Europe and the United States, and it is not clear what constitutes “bijin-ga.” It's a somewhat mysterious genre that was established against the backdrop of Japan's unique culture.

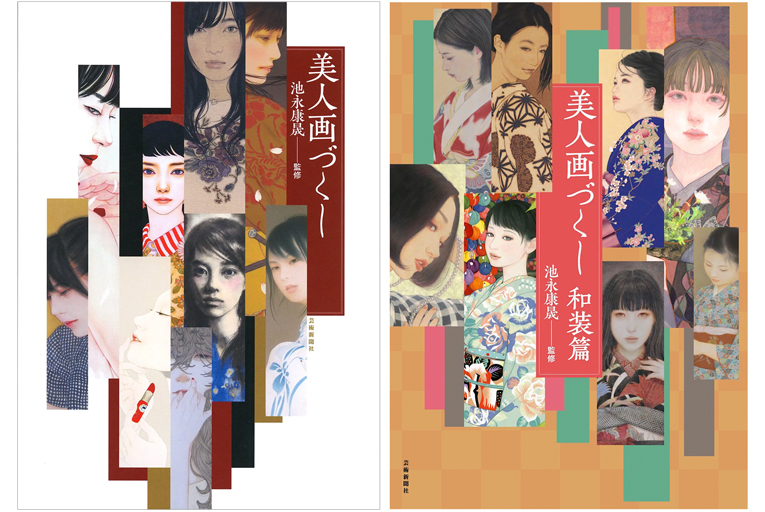

Over the past 10 to 20 years, “bijin-ga” has become popular, especially among Japanese-style painters. The painter Yasunari Ikenaga is leading the charge for “the revival of bijin-ga.” Overall, there are many female artists, and many are self-taught. There are very few people that belong to the so-called art world who went to art universities or exhibit their works in group exhibitions. As a result, artists with unique personalities are appearing.

If there is a commonality in their styles, it’s that there are relatively many lightly painted pieces. They are trying to express the beauty of women by taking advantage of the natural coloring of mineral pigments. I think they are very conscious of ukiyo-e from the Edo period and the bijin-ga in “shin-hanga” (“new woodcut prints”) from the Taisho period.

I think the recent reappraisal of shin-hanga may be influencing the direction these artists are taking. Shin-hanga, which were produced in Japan from the Taisho era to the beginning of the Showa era, were well-received. The stories of celebrities such as Steve Jobs or Princess Diana loved shin-hanga are widely known now.

――It’s very interesting that artists who were free from the systems and styles created by art school education and art contests are producing bijin-ga and empathizing with the beauty of ukiyo-e and shin-hanga. Perhaps the diversity of “bijin-ga” is reflected in the ambiguity of the term “bijin-ga.”

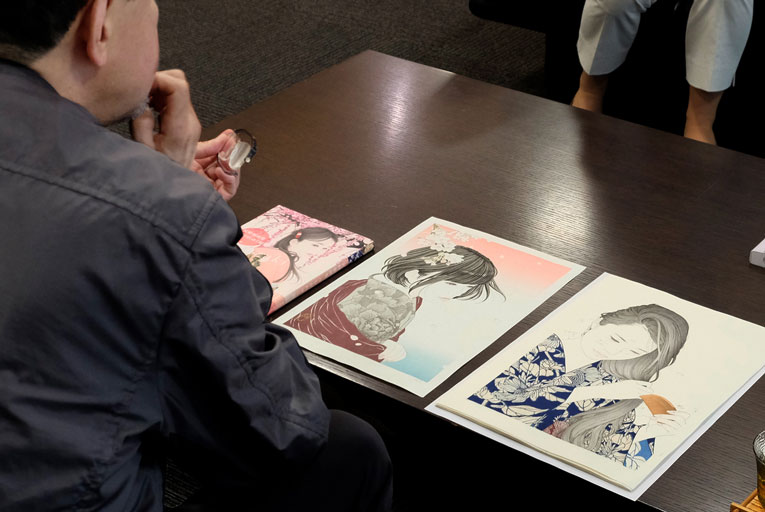

Yu Miyazaki is also completely self-taught and only started painting Japanese-style paintings in earnest in 2015, so her career in Japanese-style painting is actually less than ten years. I think it's amazing that she’s reached this level of quality in that short time. I must have been watching her work from the very beginning, but from the first time I saw her work, her work had a high level of perfection.

Miyazaki is eager to study, and I think she has an extraordinary ability to concentrate. The presence of her family, who have continued to support her artistic activities, is also a big factor.

Although there are many people creating “bijin-ga,” I think that most artists tend to create characters representing “modern girls.” There is no such exaggeration in Miyazaki's paintings. Although she depicts women in kimono, it doesn’t look old-fashioned, and her works reflect the current society. When I look at the way she paints women's nails, I think it's very modern. In that sense, Miyazaki follows the classical model of “bijin-ga,” which sets her apart from other artists.

Carrying on the traditional “elegance” of bijin-ga

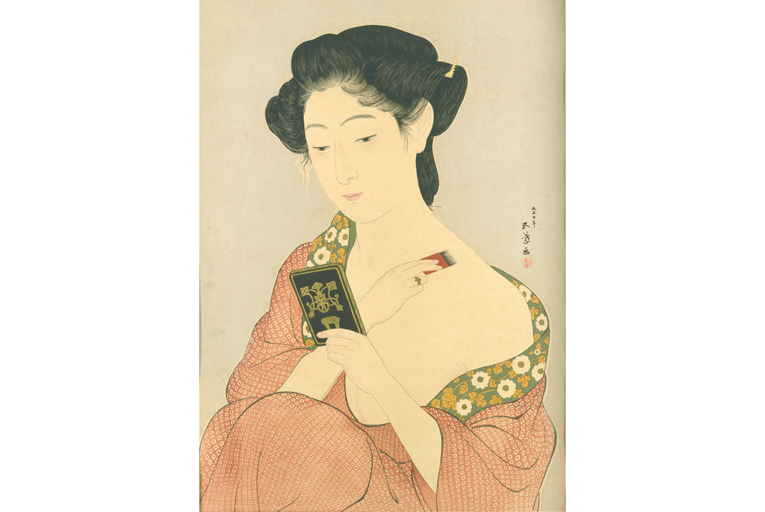

――Miyazaki's new prints pay homage to the works of Goyo Hashiguchi (1880-1921). I heard that you were involved in her encounter with Goyo's work.

The production team of the NHK TV drama “An Artist of the Floating World” (based on the novel by Kazuo Ishiguro) asked me for advice on the artwork in the drama and I recommended Miyazaki. At that time, I remember that I suggested to Miyazaki that she refer to the works of Goyo Hashiguchi. Since then, Miyazaki seems to have become particularly interested in Goyo's works. When I made that suggestion, I already thought that Miyazaki's paintings of beautiful women had something in common with Goyo's bijin-ga.

――Specifically, what do you think they have in common? Goyo himself was known as the “Utamaro of the Taisho era.” Utamaro in the Edo period, Goyo in the Taisho period, and Miyazaki in the present day all lived in different times, and there is no direct connection between them, but what has been passed down among them?

Utamaro painted many worldly women, including the poster girl of a teahouse and a courtesan, but the way he portrays them is very “elegant.” He succeeded in erasing the vulgarity from ukiyo-e, an inherently “vulgar” medium for the masses. That's what was admired by the stylish people of the time. I think this is the reason why he is one of the most highly regarded artists to this day.

Goyo, who was known as the “Utamaro of the Taisho era,” produced very elegant bijin-ga as well. He studied ukiyo-e passionately and was also involved in ukiyo-e reproduction projects. Another Japanese-style painter who painted bijin-ga at the same time as Goyo was Uemura Shoen (1875-1949). At first glance, the sophisticated bijin-ga are far from ukiyo-e, but I believe that both Goyo and Shoen understood the “elegance” that was at the root of Utamaro's bijin-ga.

And Miyazaki's bijin-ga also lacks vulgarity. Personally, I think it would be okay to show a bit more raunchiness (laughs). Her latest work also reflects the “elegance” of Utamaro and Goyo's bijin-ga.

――Goyo Hashiguchi passed away at the age of 40, and there aren't that many works he left behind. Still, Goyo is described as the “Utamaro of the Taisho era” because the images of his works were imprinted on the general public through his work on book design and advertisements, and because he produced and widely distributed woodcut prints, I believe.

That's right. Goyo designed the book cover for Soseki Natsume's “I Am a Cat.” My favorite artists, Kiyokata Kaburagi (1878-1972) and Settai Komura (1887-1940), also did a lot of work for books and magazines.

Printed products are inevitably seen as inferior to paintings, but they have a charm and influence that is different from the one-of-a-kind pieces that only a limited number of people can see at exhibition venues. And so I published a book titled “Counterattack of the Commercial Artist."

In that sense, Miyazaki's latest woodcut print could be called a “shin-shin-hanga” (“new, new woodcut print”). I think it would be good for Miyazaki to do more commercial work in the future and paint various things other than bijin-ga as well.

――As you say, in today's world where media used for expression are diversifying, traditional woodcut prints may be at the next stage of “shin-hanga.” These publications and prints expand the fan base. It would be wonderful if this new woodcut print becomes the first art piece for young Miyazaki fans.

I think so. I sometimes buy works by young artists too, and I would be happy if the purchase of their works increases the motivation of the artists and helps them become more and more active in the world.

――Professor Yamashita, you also go to exhibitions of young, unknown artists in small galleries. In the March 2020 issue of “Geijutsu Shincho,” there was a special feature titled “Bijin-ga Renaissance,” which included a section called “Yuji Yamashita's Top 10 ‘Hidden’ Bijin-ga Artists.”

Right. And Miyazaki is one of those 10 artists. But even though I do check a lot of galleries, I only find a handful of artists like the ones I introduced here.

Supporting Japanese art across the ages

――Yu Miyazaki won the Adachi Contemporary Ukiyo-e Award (by the Adachi Foundation for the Preservation of Woodcut Printing), and now she is working on her second woodcut print with modern day carvers and printers. Professor Yamashita, you have been a judge since the 4th Adachi Contemporary Ukiyo-e Award. Could you tell us about your impressions after 10 years as a judge?

This may be a request to the organizers, but I would like to see more entries as the award becomes more widely known. But every year, I come across a portfolio that makes me think, “Wow!” and I look forward to the screening meetings. I would like those who are applying in the future to be more conscious of their work’s affinity with woodcut prints.

I hope that the award winners will use the valuable experience of creating woodcut prints in collaboration with young artisans as fuel for their future artistic endeavors. I hope that it will become more effective in the future as a project that gives young artists new opportunities in a variety of ways.

At the time of application, Miyazaki had a clear motive and an interest in the technique of woodcut printing. She said, “I would like to use woodcut prints to express the appeal of kimono that cannot be adequately expressed through paintings.” After winning the award, she deepened her understanding of woodcut prints and is applying new techniques to her own work. She's a kind of artist that I definitely want to support.

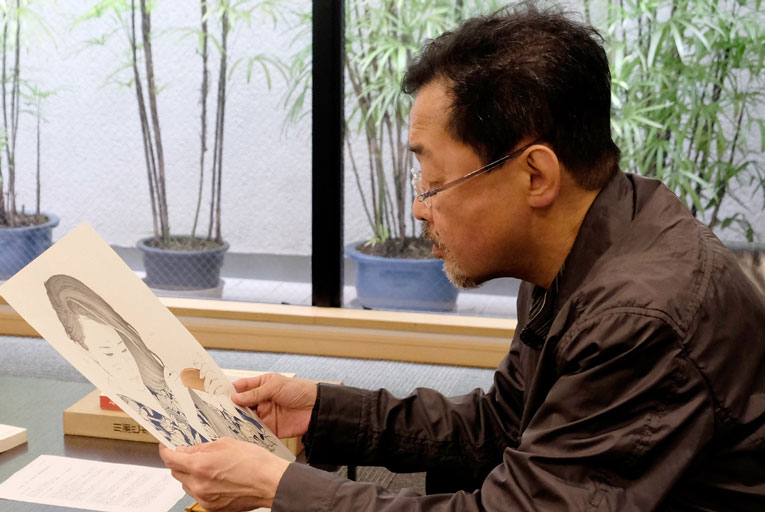

――Professor Yamashita, for many years as “Chief of the Japanese Art Support Team,” you have been discovering and introducing Japanese art from long ago, and at the same time, you have been watching over the growth of present day artists. You have always maintained a bird's-eye view of Japanese art across time.

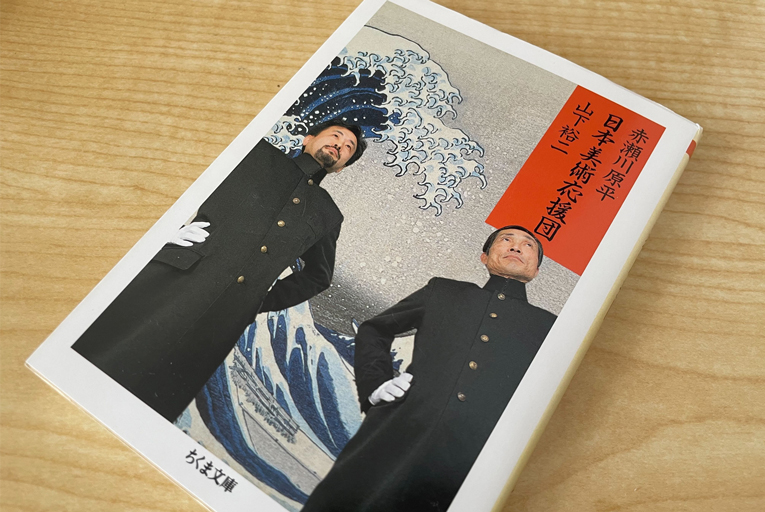

Originally, as an art history researcher, I was researching ink paintings from the Muromachi period and writing papers for academic journals. I was doing that for a long time, but gradually, I no longer felt satisfied just being inside academia. That was in my mid thirties. Around that time, I met the late Genpei Akasegawa. And I started thinking that I wanted to see all kinds of art regardless of genre, including foreign art and contemporary art.

Meeting contemporary artists Makoto Aida and Akira Yamaguchi at the end of the 1990s was also a big influence. I was shocked that there were artists who referred to past Japanese art like that. And I thought it would be great if I could do a job that was like an interpreter between the general public and the art world. Following Utamaro and Goyo, artists like Miyazaki are now creating a new style of “bijin-ga,” although their methods are different. History is connected.

Sometimes people refer to me as an “art critic,” but I have no intention of offering criticism. My job is being a supporter. I want to support outstanding art that is still unknown to many people, regardless of the era. It's like being the head of public relations for Japanese art as a whole.

When I published “The Japanese Art Support Team” with Akasegawa in 2000, Japanese art still needed supporters. The number of visitors to exhibitions was also overwhelmingly lower than that of Western art. But I think things have changed a lot in the last 20 years. I've gotten a lot older too (laughs).

――I believe that the role played by “the Japanese Art Support Team” over the past 20 years is truly significant. But I think there are still many works and talents waiting for your support. Professor Yamashita, thank you for your valuable talk today.

Yuji Yamashita

Art historian. Born in Hiroshima Prefecture in 1958. Completed graduate school at the University of Tokyo. Professor at Department of Art Studies, Faculty of Letters, Meiji Gakuin University. Starting with research on ink paintings from the Muromachi period, he conducts a wide range of research across the history of Japanese art, from the Jomon period to contemporary art. His recent publications include “Future National Treasure/MY National Treasure” (Shogakukan) and “Counterattack of the Commercial Artist” (NHK Publishing Shinsho). Exhibitions that he has planned and supervised include “The Five Hundred Arhats: Artists of the End of the Edo Period: Kano Kazunobu,” “Hakuin Exhibition,” and “Komura Settai Style.”

Interview and text: Mirai Matsuzaki (writer)

- 記事をシェア:

- Tweet